In my daily job, I sometimes work with analysing, constructing, and deconstructing political narratives. A narrative is a story – and as we know – stories can change the world.

Sometimes I find myself in existential pain, because I did not allocate enough time for the analysis bit. I feel disconnected from the stories that are already out there, I lack understanding of who claims what, and most importantly — what they are saying in between the lines.

Our politicians are often those we hold accountable for what they do. In regards to what they say, we tend to dismiss their speeches as mere publicity stunts, and consider their political discourse as full of empty words (often again, rightly so).

Discourse Analysis as Methodology and the Role of this Research

I start my research blogging journey arguing against the dismissal of political discourse analysis. Instead, I advocate for the value of studying discourse, as the narratives politicians construct in public about an issue can say a lot about the political winds of the time, and help civil society actors better navigate political change to their advantage. But what is discourse?

“[..] discourse is not just ideas or ‘text’ (what is said) but also context (where, when, how, and why it was said). The term refers not only to structure (what is said, or where and how) but also to agency (who said what to whom)”

points Schimdt (2008, in Lyngaard, 2019)

Starting with this definition, I am hoping my research contributes to the body of knowledge that better informs civil society’s strategic narrative choices. I am hoping that in my journey to dismantle techno-solutionist narratives, I will offer an overview of their making, and better tools to counter them. So what do you do with this discourse analysis, once you have it? Well, it depends on what type of discourse analysis we are looking at.

For the purpose of this research, I will be diving especially into critical discourse analysis (CDI) and discursive institutionalism (DI). With CDI, I will be uncovering the causes and consequences of discourse, but also offer a normative account of how things could be different, according to a justice-based lens. CDI offers a good tool to investigate with, as it assumes that “dominant neoliberal discourse are often – purposefully (Heinrich 2015; De Ville and Orbie 2013) driven by political elites and, while being favourable for certain economic and political elites, they also cause political, economic and social marginalisation.” (Lyngaard, 2019).

The method I will use to conduct CDI is through media analysis. I will be using a media scraping tool with pre-assigned keywords and selected “storyteller” politicians. I will combine critical discourse analysis with a short institutional research, to empirically map political messaging intended by the institutions towards their stakeholders.

Techno-solutionism as a topic, part of the Climate Delay Discourse

We’re at my place, one Thursday evening some years ago. With my left hand, I was munching on some popcorn and with my right on the mouse, browsing through the website of the Green Web Foundation. As I was digging, I stumbled on the Green Web Syllabus, an awesome collective resource of readings. The “narrative” section was an organic magnet for me and so I found myself munching on more than popcorn.

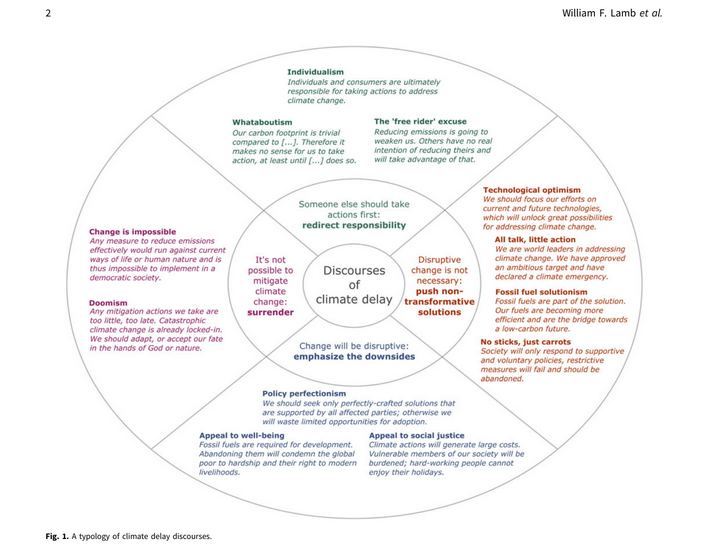

Lamb et al.’s “Discourses of Climate Delay” (2020) is a piece that maps and categorises the claims used to acknowledge climate emergency, but postpone its radical address by justifying inaction of inadequate efforts”. Within discourses of climate delay, “technological optimism” is part of those types of narrative for which disruptive change is not necessary, and which instead push non-transformative solutions (Fig. 1 – A typology of climate delay discourses).

For the readers involved in digital rights and critical investigations around the digitalised society, “techno-optimism” is what you’d traditionally call “techno-solutionism”. For those unfamiliar with the term, through it technology is seen as a bullet-proof solution to anything. It is often adopted by tech entrepreneurs trying to sell their tech (“I have the tech solution, let’s find a problem to solve”) or by politicians eager to show their electorate they’re active in finding “solutions” to structural problems when in fact implementing inefficient public-private expensive partnerships.

I thought – wouldn’t a deep-dive into techno-solutionism alone be quite exquisite? Oh, yes, yes, yes! How about we submit a proposal to the upcoming fellowship? Sounds good, hi5 dear choir in my head. And here we are.

Anomaly 1: The growing EU – Latin America relationship focused on raw materials

Initially, I thought it’d be worth looking broadly into techno-solutionism within EU politicians’ discourse. But then I remembered the conversations I had with digital and climate justice community leaders around RightsCon Costa Rica and the subsequent gathering organised by the Green Screen Coalition. While there were many overlaps in the narratives we all faced, there were also very different, often more creative approaches, folx from Chile, Argentina, Brazil were telling me about. I thought “Damn, we are really boring back in Europe” which, I know, is not novelty – but it was still a painful reminder.

“The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not ‘Eureka!’, but ‘That’s funny …’”

Isaac Asimov

I came back home and started tip-toeing on the interwebz, trying to understand the public narratives available to a person like myself (white, cis woman, Romanian in a Western European capital, medium understanding of Spanish). As I was browsing, I was finding a lot of news about the EU’s growing relations with the countries I just mentioned. I was especially discovering the EU-Mercosur trade agreement, intense visits of EU and Brasilian officials into each others’ yards, a new Memorandum of Understanding EU – Argentina on sustainable raw materials value chains, as well a different Memorandum on the same topic of raw materials between EU and Chile.

Hmm.. curious.

It is such moments of curiosities that have actually helped scope my research. Some people call these “curiosities”, “anomalies”, and anomalies are often the root of discovery.

Anomaly 2: A push for the “green-digital transition” in the middle of a security crisis?

The increasing EU – Latin America relationships came on top of a previous “That’s funny” thought I had.

In 2018, I first heard about the intersection between environmental and digital when I interviewed a dude involved in a Danish – Estonian green energy grid project. Politically though, the environmental and digital transitions were not associated at EU level as part of a synchronised political agenda. In fact, politicians’ agendas were barely dominated by digital policies and the world was waking up from mass denial, to finally acknowledging the environmental situation as a crisis.

Oddly, the 2019 pandemic changed that.

Within the EU and across the world, political leaders realised digital is an underlying infrastructure for everything. They also realised our dependencies on private conglomerates , corporations, owning this digital infrastructure. In 2020, the message was simple: we need data, but we want to move away from data monopolies and towards strategic autonomy.

“We still need a significant leap forward on data collection and governance for economic and societal benefits. In turn, this calls for a ‘European way’ of governing the use of data, not least to avoid data monopolies”

European Commission, 2020 Strategic Foresight Report

With the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the health crisis turned into a security crisis – not least with its cyber attacks component. In solving this security crisis, the political wind turned towards digital solutions (perhaps also encouraged by China’s declared focus on developing AI for military deployment). However, our politicians needed a better PR exercise than “security” arguments.

As the climate crisis was finally acknowledged (more or less) across the political spectrum, “digitalisation in the service of the planet” became a comfortable political discourse to sell voters, as a story no political formation would counter. And this, ladxs and gentx, is how the political momentum for the digital-environmental twin transition peaked.

In its 2022 Strategic Foresight Report focused on the “twin transition”, the European Commission makes the connection clear. The paper points out that the security crisis reinforced the need for raw materials, surprise, also needed for the twin transition. Hah, much stars alignment, much wow, what are the odds?

“The current geopolitical shifts prompted by Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine are renewing the sense of urgency to accelerate the twin transitions, and to reinforce the EU’s resilience and openness. They also enhance the need to secure access to critical raw materials, needed to feed the twin transitions and for which the EU is still highly dependent on third countries.”

European Commission, 2022 Strategic Foresight Report

Connecting the dots: EU’s military (not green) tech to be built in-house needs critical materials from Latin America – who pays the price?

And, how can we counter this publicly without being accused of standing against environmental justice?

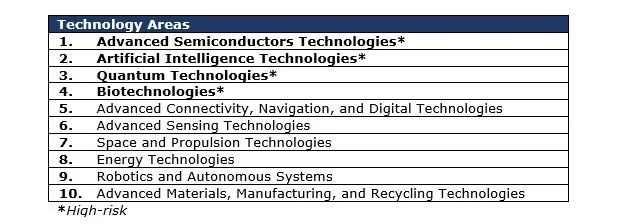

In 2023, the EU defined and agreed to assess the risks of 10 Critical Technologies, out of which 4 are high-risk, intended to be built “in-house”, in order to secure its strategic autonomy and economic security. These were advanced semiconductor technology, artificial intelligence, quantum and biotech. The list of critical technologies focuses on those with an “enabling and transformative nature”, beyond dual-use technologies .

With this context filled with anomalies, the next steps of my research would benefit from some answers to the following questions. Dear reader, ping me if you have ideas!

- What are the main claims that make the “twin transition” an agenda point accepted across the political spectrum?

- Have such narratives already manifested in other countries such as Chile, Argentina, Brasil, Bolivia?

- With whose natural resources will the EU’s “green technologies” be built?

- With whose natural resources will the EU’s “dual-use” / critical technologies be built?

- Who are the people (EU, Argentina, Chile officials) shaping the public narrative around the EU’s advancing critical raw material supply chains in Latin America?

- What are the points of agreement and those of discontent between these voices?

- What is the impact on the communities most-affected by EU’s new agreements focused on sourcing critical raw material from Argentina and Chile?