Earlier this month the 2024 edition of the HTTP Archive’s Web Almanac was published – our industry’s bi-annual “State of the Web” report. This is the second edition with a chapter focussed on digital sustainability, and the second using our Green Domains dataset. In this post we share some of the key highlights and takeaways from the report.

For those new to it, what is the Web Almanac?

Different industries have a definitive State of the Industry report that comes out more or less each year.

For people who build the web, the Web Almanac is that report – an authoritative document representing hours and hours of analysis. It covers trends that have developed in the industry since the last publication, as well as providing an overview of what you need to know as a web professional about where trends are going.

You can see the full report on the HTTP Archive’s dedicated section of their website.

What does it have to do with digital sustainability or the Green Web Foundation?

Back in 2019 when we started opening up parts of the Green Web Foundation, from open sourcing the platform to publishing our datasets as open data, there was one thing we weren’t sure we would ever achieve but would love to see happen. We wanted the datasets we published to be used in industry benchmark-style publications.

We said this:

One goal in particular that we have is to create a dataset that can easily be incorporated into existing resources like the HTTP Archive – so when we talk about the state of the web, we can also talk about how much of it runs on green power, and how much still runs on fossil fuels.

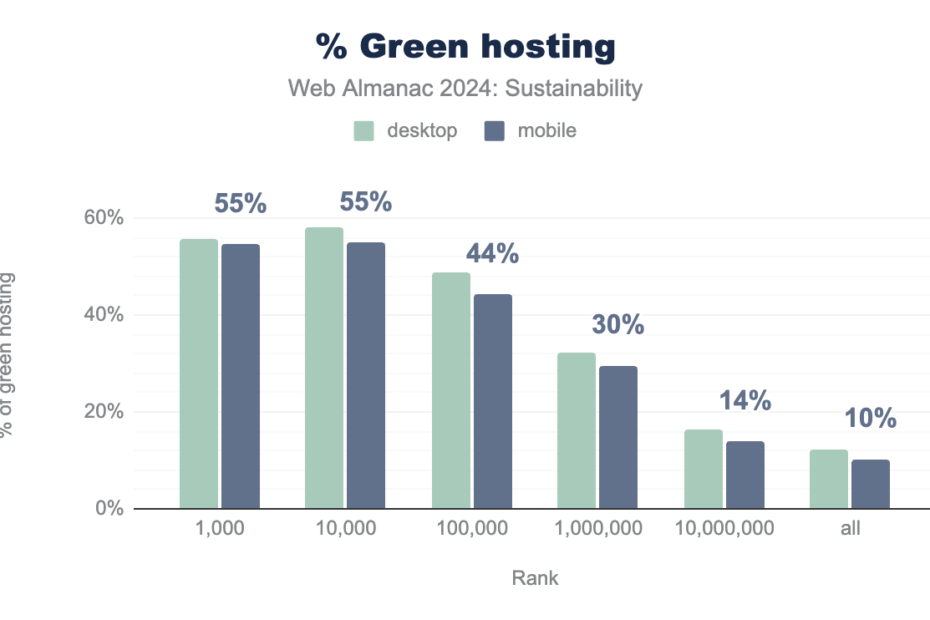

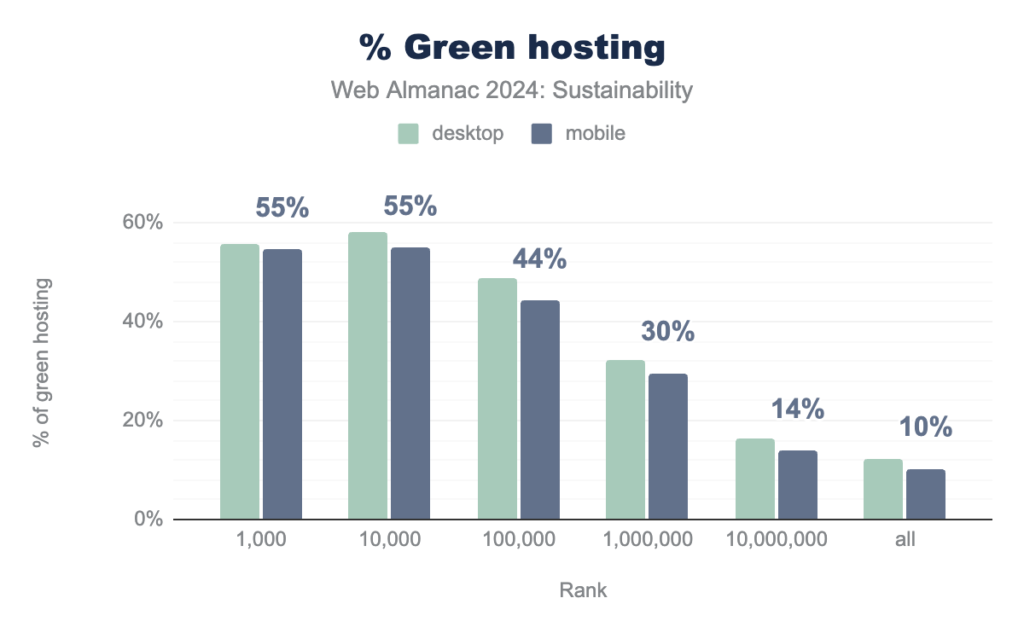

Fast forward to today, and 2024 Almanac is the now the second edition of the Almanac to use data like we hoped. To be honest, it’s really nice now to be able to point to cool charts like this, of the HTTP Archive incorporating our data into their analysis.

We think it’s interesting, sure, but it also helps give us an idea of how the transition is working out – something crucial if we want a fossil free internet by 2030.

What does this chart tell us?

Well, one immediate take-away is that for the largest sites on the web (as in the top 1000 sites), the transition is well underway – more than half of these sites show up as running on green hosting – huzzah!

We do see this drop off as we cast the net wider, to check the longer tail of websites. This is not a surprise, and it could be a question of coverage in our dataset as much as smaller website providers moving less quickly on climate. It’s also worth understanding that there is a significant power law in place as you go down the list, so sites outside the top 1000 receive much less traffic than the top 1000. This means that looking at just domains is not the full picture – it’s likely that the bigger websites use much more infrastructure and energy than the small ones.

We think it does raise a query about how cleaner energy on the web is procured though – for large companies, clean energy frequently represents a saving, but for smaller firms it’s often an extra cost. This is because small firms aren’t able to do the same large-scale custom energy deals that large firms can do. You heard about those big news stories with Microsoft, Google and Amazon investing in nuclear power? In the US, it’s likely that half of those energy costs will be paid for by the US government through subsidies and tax credits. Here’s the part of an interview with the head of the current US loan programme office explaining how that works (jump to minute 48). So for every dollar being paid in these deals, a dollar is being directed away from education and healthcare to help pay the energy biills of tech firms worth literally trillions of dollars.

Smaller firms have it different. They either have to purchase energy a green tariff that is typically priced at whatever a utility is able to get away with pricing it at, or they have to purchase power, and then separately try to purchase some kind of certificates independently to so they can mark their use of power as green.

There are all kinds of issues with this, and we’ve covered this in detail in an earlier post – who pays for cleaner energy on the web, as well as in our recent response to the GHG protocol’s consultation on Scope 2. If we want to see more of the long tail turning green, we might need different policies to make this happen.

So, what else is there?

Other highlights

The sustainability chapter is a formidable one – it’s more than 17 thousand words! Here are some of the highlights and non-obvious ones:

We can’t always rely on the grid getting cleaner each year

For years and years, you could rely on the grid getting greener each year, especially since the 2010’s. However, in the figures used since the last report, the average carbon intensity for the entire world is actually slightly higher than previous years, bucking the trend.

The analysis in the Web Almanac does not use the carbon intensity of 2024, because those figures are not widely available yet, but we know that there was a perfect storm of a post-covid bump in demand globally for energy from 2022, and the Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also led to restricted supplies of natural gas, which at the point of burning at least has a low carbon intensity than coal, which filled in in various places.

We do expect the carbon intensity figure for 2024 to be lower once again as soon as we have the data for a full year. Every month, we merge in the latest carbon intensity figures in CO2.js, based on the latest analysis from Ember Climate. If you use CO2.js in your project, you’ll have access to these figures.

The state of the law in digital sustainability

The sustainability chapter also does a good job of covering various developments in the law since 2022. New laws in France, Europe, India and so on all get some coverage, and if you haven’t been following the evolving policy landscape around digital sustainability, it’s a useful roundup.

Most websites are getting slightly smaller

Finally one guarded piece of good news is that most websites are ever so slightly smaller than in 2022. We’re not sure why this is the case, and in many ways celebrating it feels a bit like celebrating the incremental process we also see on climate when we know it’s nowhere near what is necessary.

Still, we’ll take it! Some weeks can be good weeks for climate, and some weeks can be bad ones. In a month where we’ve seen some really challenging news climate-wise, sometimes you have to take what you can get.

Where to learn more

You can read more about the current and previous editions of HTTP Archive’s Web Almanac, as well as how it is created on the HTTP Archive’s dedicated website.