When we make broad subjects collide, and most importantly, when these subjects address a wicked problem, it’s hard to get a grasp of where to begin untangling it. As I wrote for my introductory post, I believe that all disasters can be addressed from a human perspective (either as victims or perpetrators) as a way to connect from the standpoint of a narrative. For this reason, I want to look at the first objective of this fellowship and start thinking of some of the elements I want to address in the next few months.

We want to explore compelling narratives that link responsible Internet practice with climate justice. This narrative is an important step to better defining the issues, identifying the most impactful interventions and galvanizing partners.

Before thinking about the final result of this fellowship, which could be some sort of syllabus (or learning product), we want to think of the narratives to connect the role of Internet practitioners and environmental justice. One way to get started is to think about some of these concepts. But for now, let’s talk about environmental justice, which is probably the concept I find the hardest to wrap my head around.

If justice falls in a digital forest and no one is around to hear it…

In short, justice is about establishing and maintaining good relationships, either among fellow humans or with nature. The Internet promised from its beginnings and still promises through the concept of an open-architecture network, a broad set of possibilities to connect to a network that “can be designed in accordance with the specific environment and user requirements” (Leiner et al., 2009). This means that anybody can build whatever suits their needs and connect to the network, and despite the technical connotation of this concept of “environment”, it stands that there’s an interdependence between the physical and digital layers of the Internet.

When we consider the global reach and extent to which the Internet is part of human activity, this connection between the non-physical (let’s call it that to not go down the rabbit hole for now) and the physical becomes either too connected and disconnected at the same time, all through the lens of solutionism, or the view that all problems can be solved with technology, including climate change or other environmental issues (Tucker, 2013).

It leads us to center human activity, including the problems of our environment through the Internet, starting from the perspective that we will never do away with it, and that the only path for it is to become bigger and hungrier. One analogy is to think of solving urban traffic as we sit in traffic. Are we allowed to consider the problems of human activities we take a part of while being part of the problem?

We should by no means believe, that since we take part in the problem, we’re disqualified from taking a part in the solution. But it does mean that we must check the privileges that we possess, and start thinking about those affected by our activities, including the environment, to develop the structural solutions that we need.

A separate justice

At the same time, it is possible to claim the opposite of this. When J.P. Barlow wrote A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, in his mind (and of those who followed him), cyberspace was a conceptual space that was born and could remain completely detached from the material world. “They are all based on matter, and there is no matter here,” he wrote in regards to this idea of an immaterial world, and in regards to justice, “you do not know our culture, our ethics, or the unwritten codes that already provide our society more order than could be obtained by any of your impositions.”

Despite the partial, and practical validity of these statements at the time when this was written about an Internet whose energy usage was negligible in comparison to the monster that it has become. Today, we can assert without a shadow of a doubt, not only that the Internet must be seen beyond its immaterial impact, but also that it exerts a real impact on the environment because it increasingly requires energy to survive, and depends on an environmentally dependent infrastructure to maintain the modes of communication that we use to communicate.

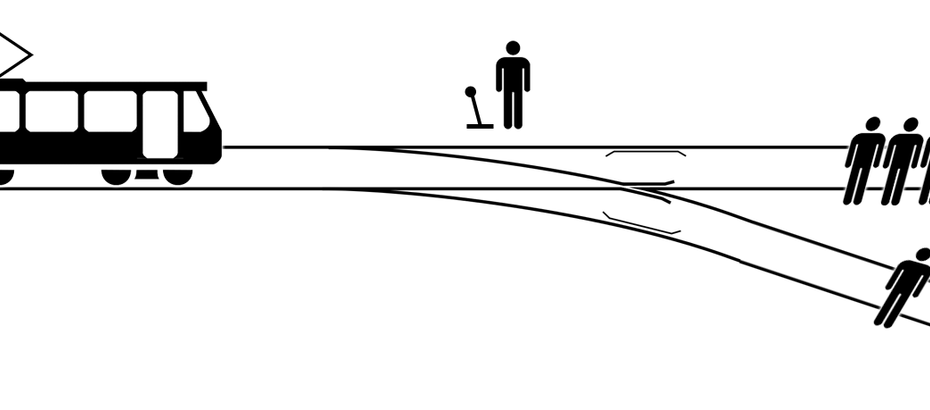

Despite this, it is easy to separate our activity on the Internet and the impact that it brings. A good way to think of this is the trolley problem that you might have heard of, which poses a tough moral burden by forcing you to make a decision that will cost human lives. Interestingly, the human mind is able to relieve some of this burden from the consequences taking place in front of us by adding a cold, mechanical lever. It doesn’t feel as bad when we make that decision through a mechanical device, which could very well be a lever or a button. I pose that a mouse click is all the same, for that matter.

This reality of the human mind bears grim consequences as we consider how our use of the Internet is affecting the environment: as we adapt our digital infrastructure and practices through millions of levers put in place through shiny web UI, or even physical transistors, it is easy to forget that a boundless-growth mentality is affecting the physical environment around us.

Narratives make sense

For this reason, as we move forward in the exploration of narratives around the Internet, fossil fuels and environmental justice, some of the important ideas to address might be:

- As human activity on the Internet becomes irreversibly digital (since we’ve decided to do so), the environment risks will continue to grow and create effects in our lives.

- We can measure the impact of online activity by individuals and organizations, which mean that we are accountable for our decisions in the digital world.

- Even through ignorance, we all are taking a stand around the environmental impact of how we use Internet as we choose technologies, standards and services online.

- We must chose the future that we want on Earth and connect it to how we live online and how we help shape human activity online.

- We are all responsible for creating a just society, online and offline.

References

- Leiner, B. M., Cerf, V. G., Clark, D. D., Kahn, R. E., Kleinrock, L., Lynch, D. C., Postel, J., Roberts, L. G., & Wolff, S. (2009). A brief history of the Internet. ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review, 39(5), 22–31.

- Tucker, I. (2013, March 9). Evgeny Morozov: “We are abandoning all the checks and balances.” The Observer. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/mar/09/evgeny-morozov-technology-solutionism-interview *Koebler, J. (2021, October 28). Zuckerberg Announces Fantasy World Where Facebook Is Not a Horrible Company. https://www.vice.com/en/article/qjb485/zuckerberg-facebook-new-name-meta-metaverse-presentation