This post has been written by PhD/Dre. Rub(én) Solís Mecalco as part of their project funded by the Green Screen Coalition Awards, of which Green Web Foundation is a contributing member.

The postcolonial, antiracist, intersectional and non-binary gender approach applied to the project ‘Equalizing access to climate change information and digital tools for rural Mayan communities’ allowed an incredible collective journey of continuous learning and sharing process within the Yucatecan Mayan communities.

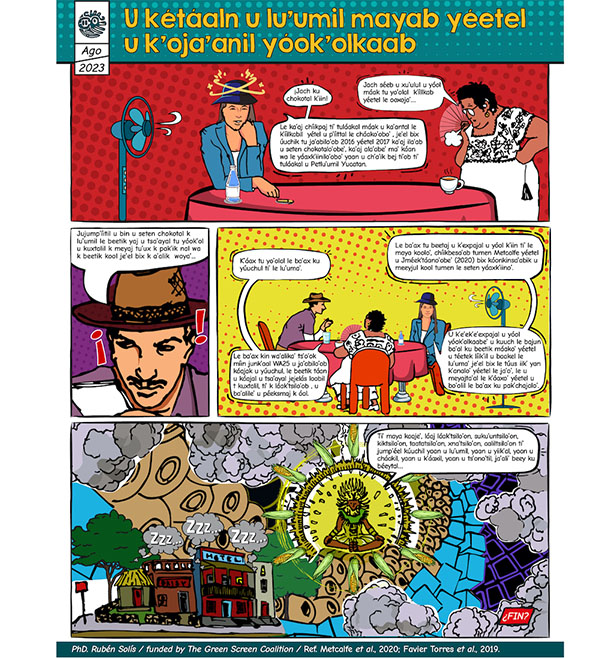

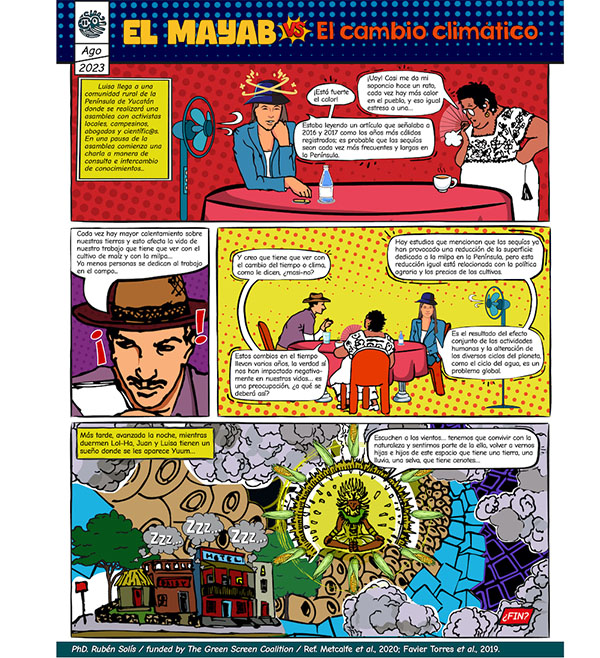

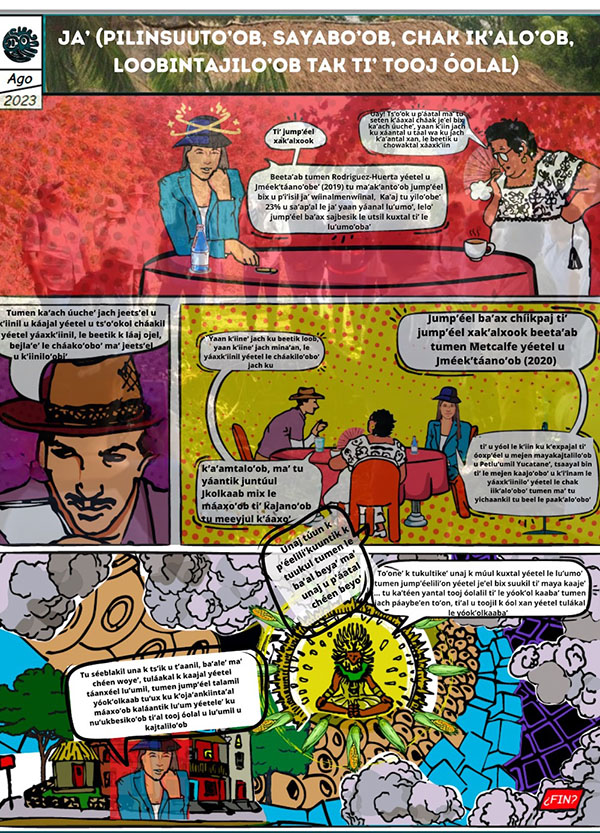

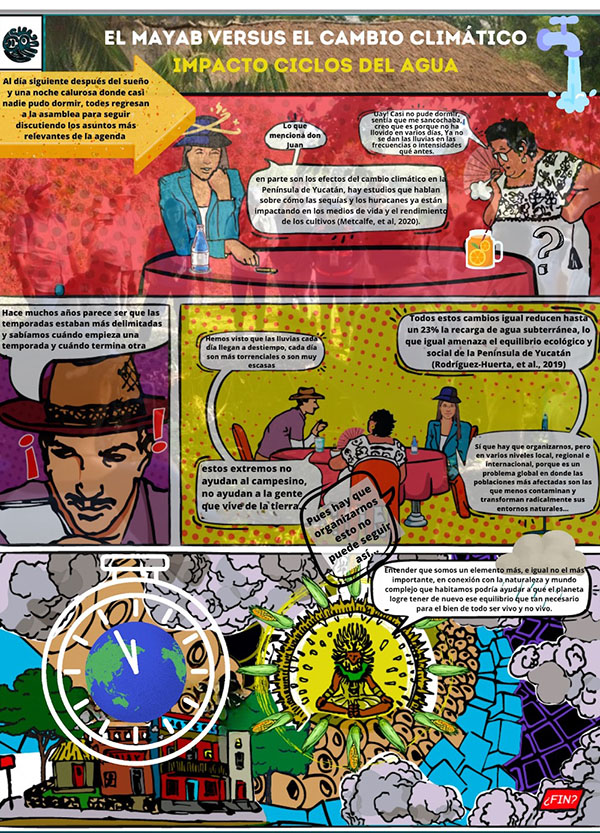

This project resulted in the publication of a set of infographics with an accessible narrative in Spanish and Yucatecan Maya, reliable information, eye-catching designs, and available in digital and print format.

These formats were developed as digital tools to spread information and democratization of scientific information about climate change to historically and systematically marginalized indigenous populations. Information that will be also helpful to make local decisions about this complex global phenomenon.

The infographics

Heat

Water

If you want to see or use higher resolution versions of these infographics, they are available on my Google Drive.

The process

The first phase of the project involved researching information about climate change impacts in the Yucatan Peninsula in the last five years. Even that task implied a lonely moment of the project. The digital interactions with different members from Mayan communities, between activists, artists, campesinos (farmers) and local leaders about how they felt and interpreted the impacts of climate change in their daily life and main activities (economic, social, cultural) – all of them connected with the nature around.

This gave me more light to focus in two specific issues in the sea of knowledge:

- impacts of climate change on the heat/increasing of temperatures;

- impacts on water resources.

In this sense, developing research of scientific literature already being aware of the information gaps, and the needs of the local communities was helpful. The main audience for this project were the Mayan rural and urban communities.

With a clearer idea of the challenges on the horizon, the process of synthesising the information started. At this point I decided to incorporate some anonymized extracts of conversations that I had with local leaders.

The translation process happened in different layers – English to Spanish and Yucatecan Maya. It’s important to remember that most of the scientific articles about the region are published in English, and the fact that scientific redaction can be technical and hard to understand for a bigger audience.

These questions appeared:

- Which audiences can already access literature about climate change in the region?

- Is information accessible for the mainstream population and/or for the Mayan rural communities?

The lack of information in the communities was based on the limited, up to date literature written in local languages without a hyper-technical english narrative. This proves again that scientific literature, even in open access, is not written to be accessible for indigenous communities. And at the same time, they are one of the most vulnerable populations to climate change impacts

Not just to the scientific information. Most of the articles and books that I cited for this project are available in open access. The problem was that all these articles are written for other technical scientists or scholars, not even for social scholars. The other problem was the predominance of English literature about the region. In this context the translations process was most important to build knowledge bridges.

I need to acknowledge my translators between Spanish to Maya, and the main designer who helped me. Together we edited the texts that finally were incorporated in the Infographics and ensured they were written in a friendly narrative in the local languages (Spanish and Yucatecan Maya) for people without deep knowledge on climate change and its local effects.

The visual task was another collaborative process between local assemblies in rural Mayan communities, the designers, and me, here the results are in ‘comic’ format.

Is important talk about the right to not just get access of scientific and actual information about impacts of climate change on indigenous languages, but also the importance that these tools (digital or print) can be also visually interesting and link with the local situations and contexts, catching the attention from locals and people around the world.

Workshop

Beyond the importance of using different social media and digital platforms to share these digital tools, the workshop in collaboration with Múuch’ Xíinbal Mayan Assembly members in the rural Mayan community of Chunhuhub, Quintana Roo with more than 15 participants, was particularly powerful and significant.

In this Mayan safe space for all sex-gendered identities, I shared the digital and print version of the infographics to members from different Mayan communities in that region of Yucatan Peninsula. I learned from the feedback about possible next steps to develop the goal of continuing this non-stop process of sharing reliable information about climate change for local audiences.

Finally, I want to say that this project was a continuous and collective way/process of hearing, learning, and sharing. Thank you to all the members from Múuch’ Xíinbal Mayan Assembly and Green Screen Coalition to make possible this project.