In a recent post, we shared a few lessons learned from working with our friends at Wikirate to understand how much of the internet was covered by credible net zero targets. We described how hard it could be to crowdsource meaningful data about the climate ambitions of the largest firms online and why this was the case. We also hinted at carbon.txt—a new project we’re kicking off to improve the discoverability of sustainability data thanks to funding from NGI Search. In this post we outline how carbon.txt aims to address these issues and where you can get involved.

The TLDR version

- Discovery of sustainability data continues to be a problem. Our research with Wikirate made it abundantly clear that without new, webby approaches, sustainability data will continue to be hard to find or out of date.

- Changes in the law mean that lots of firms will need to publish all kinds of sustainability data that previously they didn’t have to. The law literally says they need to publish this data online, free of charge for the public to see, and there are significant GDPR-scale fees for non-compliance.

- New standards mean that this data will be comparable, machine-readable, and likely across different parts of the world. This could make verifying claims and identifying greenwashing easier, if it’s done right.

- Carbon.txt is our open-source project to make this sustainability information easier to discover. Carbon.txt is a spec that defines predictable, consistent places on any website to publish sustainability data so that both humans and machines can find it.

- We’re looking for technical experts, policy makers and people responsible for sustainability disclosure in firms affected by the CSRD to talk to. You can express interest via the linked form at the bottom of this post.

Why do the net zero targets of internet companies matter?

The Green Web Foundation is oriented around the world reaching a fossil free internet by 2030. For this to be possible, the firms that make up large parts of the internet need to do two main things:

- Make clear public commitments to reduce their carbon emissions

- Follow through on their commitments with meaningful action.

In an earlier post, How much of the internet is covered by credible Net Zero targets? What we learned we go into more detail about why we think these are necessary.

Focusing on the first step—clear public commitments— it turns out that reliably finding credible data by itself is already a challenge.

In our work, we found that finding the data needed to tell if company commitments were credible, even when it was published online, was not easy.

We also found that the inconsistency of data made comparisons between each firm extremely challenging.

Finally, one of the big challenges was simply that for many firms, sharing any information about their climate plans was seen as optional. Transparency was seen as a nice-to-have, not a must like the kinds of financial reporting that firms publish without fail each year.

In the end, we found only one firm out of the top 20 with clear, public, interim Net Zero targets with clear numbers you could refer to in future.

We know that the science on climate is clear. We need rapid, far reaching, unprecedented changes to avoid more of the deadly heat, flooding, fires and other harms brought about by a warming world.

We also know that given the resources available to large firms, and the significant environmental footprints of their operations, this transparency is needed for data-informed public discourse about how we meet our climate goals.

What’s changed since our initial research?

It’s worth noting that we were researching in 2023 for information for the reporting years of 2021 and 2022. It’s 2024 now. Has anything changed?

In a word, yes. Here’s how.

1. There are new laws that make sustainability reporting necessary, not a just nice to have

The biggest change in the last 12 months is new legislation passing that requires companies above a certain size to report environmental data each year like they do for financial data.

One of the best examples of this is the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive passed in the European Union, otherwise known as the CSRD. Plan A’s summary gives a good idea of how big a deal this is, and what kind of information that companies will need to be reporting for the first time.

The CSRD Directive (clause 55) literally says, “Users of sustainability information increasingly expect such information to be findable, comparable and machine-readable in digital formats. Member States should be able to require that undertakings subject to the sustainability reporting requirements of Directive 2013/34/EU make their management reports available on their websites, free of charge to the public.”

If you aren’t au fait with how laws in Europe work, this can feel a bit abstract. The short version is that once directives are passed and agreed upon, it’s until they are written into the national laws of each country that we really understand their full impact.

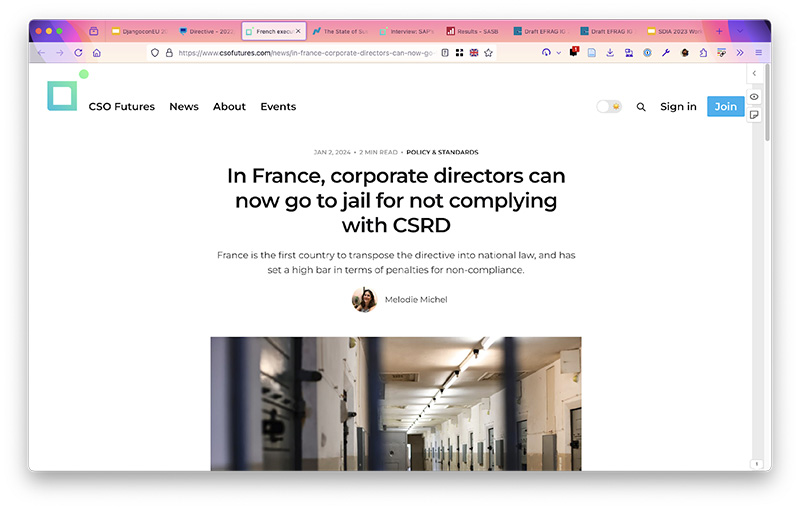

Liberté, Egalité, CSRDé

Earlier in France we had our first taste of what this might look like, and their law went slightly further than what was agreed in the directive. These laws are turning out to have real teeth.

Just like how firms had to scramble to respond to changes in the law brought about by the GDPR privacy law, it looks like something similar will happen with the CSRD.

It’s not just in Europe that we are seeing this trend. In California, the largest economy in the United States, the Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act (the CCDAA) was written into law late last year, which in substance is similar to the European CSRD.

At a national level in the United States, the Securities and Exchanges Commission (the SEC), has also mandated climate reporting. The SEC is the body that regulates what publicly traded companies in the USA must report each year, so this is a significant shift.

Together, these legislations are making it mandatory, not optional, for larger companies to publish sustainability data. That’s a big change.

2. Consensus is forming around what needs to be reported

While it’s a step forward to move from optional to mandatory reporting of sustainability data each year, you still need the information to be comparable and consistent if you want to use it. Fortunately, we are seeing progress here as well.

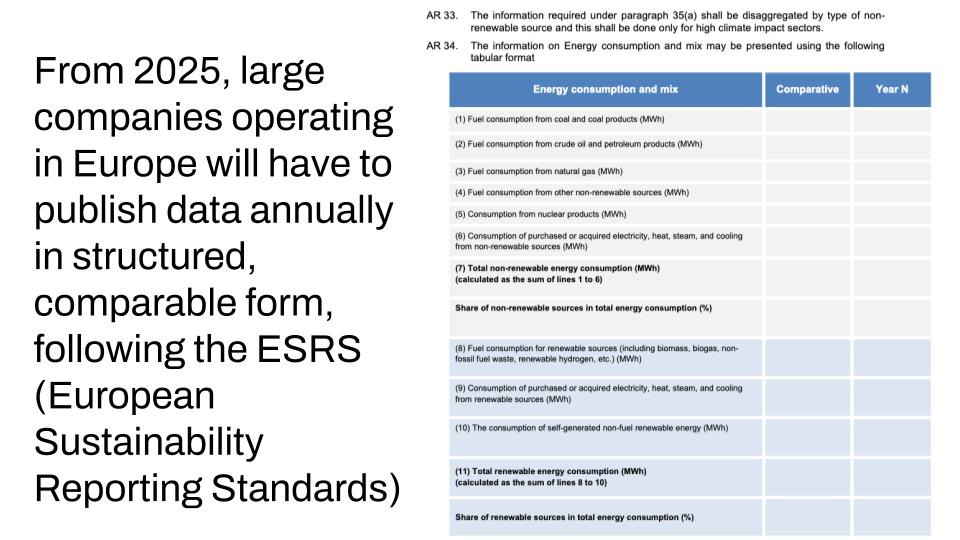

In Europe, when the CSRD was passed, there was a parallel effort to define some meaningful standards for reporting.And after many, many, many meetings, we have the first set of European Sustainability Reporting Standards (the ESRS). These set out in detail what kind of information should be reported, what units to use, and so on.

These cover a wealth of data points. For an NGO that cares about a fossil free internet, these standards are very helpful, as they include the kind of information we might ask for ourselves in our own verification process.

This isn’t just a European thing though. We know that for regions outside of Europe, there is ongoing work to make the data published in Europe interoperable with other countries. This helps avoid duplicated work, and also means code used to process data sustainability data in Europe is more likely to be reusable in other parts of the world, too.

Finding consensus around Net Zero

While this isn’t our primary focus, we are seeing movement around Net Zero as a concept, too. Just last month, we saw an announcement by the British Standards Institute to finally start an international process to define an independently verifiable international standard on Net Zero, based on freely available guidelines in the public domain by the International Standards Organisation.

What hasn’t changed since our research?

It’s not all good news though.

1. Discovery is still unsolved

We know that firms will need to publish data that they historically haven’t had to. In various parts of the world there will be large enough penalty measures for not disclosing information to motivate action.

However, if published data isn’t easy to find, the act of publishing can be somewhat academic.

Simply put, you can’t find the data an organisation is publishing, then you can’t use it.

This is also a problem in the context of these new laws. If it’s difficult to tell whether an organisation has published the data they should be, (and in Europe the law literally spells out that companies need to publish this on their websites now), then it’s hard to tell if the law is being followed – which is a problem for enforcement.

A knock on effect here is that if third parties can’t independently verify that firms are publishing data when they’re supposed to, it’s also easy for data to be delayed coming into the public domain.

This isn’t good for data-informed public discourse. If only one side of a debate, particularly the one profiting from and often causing the environmental harms, has exclusive access to the necessary information for an informed discussion, then we are unlikely to reach fair and equitable outcomes.

2. Collecting, not connecting

At present, where there are new laws mandating disclosure, they are focussed around disclosing to a centralised portal. Or in some cases, a database that is yet to be specified, let alone built.

In Europe specifically, it looks like we’ll see national databases set up for each country, that will eventually be published to a single, Europe-wide access point. It’s not clear how often updates will be made available to the public or how much it will cost to access this data programatically.

There are very good reasons to have centralised databases, but they can often be slower and less transparent than alternatives. For context, in Europe, the target timeframe for making a centralised, European-wide database available is the summer of 2027.

Two cheers, not three

So, to summarise, there is good news about disclosure and standards. But this good news is tempered by some less-good news about how easy it is likely to be to discover and use all the new information that firms will need to publish.

Fortunately discoverability is a problem that has been solved on the internet many times over the last 30+ years.

We also think that it’s possible to move faster and make disclosure more transparent than it would be with just a single centralised database.

Introducing carbon.txt: An open, decentralised approach to sustainability disclosure, starting with green energy

Carbon.txt is our open-source project to make sustainability information easier to discover and use.

Through our carbon.txt project we propose a standardised, yet distributed place on website domains, to efficiently surface the structured data that companies now have to publish anyway.

Carbon.txt would become a single place to look on any domain for public sustainability data relating to that company, that would allow anyone to build a database.

Our aim is that a carbon.txt file would become a widely known place to look on any website domain for public sustainability data relating to that company.

For example, a user could visit domain.com/carbon.txt to find sustainability data about that company.

Cultivating a new data ecosystem

We can see an entire ecosystem growing around all this data that is newly discoverable, structured data and also now in the public domain.

Useful for us, but useful for others too

For example, we are an organisation focussed on green energy, and would like to use some of this data to make our own verification processes more efficient and transparent. But we wouldn’t be the only ones benefiting from easy, timely discovery of this structured data.

To get an idea of the kinds of work we might see, you only need to look the thousands of questions people are trying to answer using manually compiled sustainability data about companies on Wikirate.

Civil society organisations can use this to highlight good practice among firms and improve local engagement. For example, in the UK, local councils have had an obligation to share their climate plans and progress for a while, and mySociety has successfully galvanised civic engagement with local councils by using this information to create their Climate Action Scorecards.

It’s not just civil society though. Search engines could index this information, to present the insights gleaned from the published data alongside search results, to help inform purchasing decisions. The sustainability focussed search engine Ecosia does this at present, helping nudge users to greener decisions. This is currently done through significant manual effort at present. As a result, they can only do this for a handful of companies, rather than the thousands covered by the new laws.

This can even be helpful for the governments building the centralised databases we spoke about in the first place. If there are open, reliable, ways of verifying that correct, structured data has been disclosed by the firms being regulated, then it’s possible for them to import this data themselves.

The key difference is that it lets all of us see whether companies are disclosing what they should, when they should.

Kicking off our newly funded research

As mentioned in our wrap-up of the research work we did with Wikirate, we’ve been awarded a grant by NGI Search to help address this discoverability problem. Starting this month we begin work on extending carbon.txt, a project to define a machine-readable way to disclose green claims using existing governance structures, published data, and industry standards.

Let’s unpack that, in the context of the green claims our Green Web Check service is known for.

A machine readable way to disclose green claims

We say a machine-readable way to disclose green claims, because that’s essentially what our verified green check services help organisations do. We help organisations disclose that they are running on digital infrastructure powered by green energy. We make this information available via various machine readable ways, like our APIs, and datasets.

Using existing governance structures

We verify information manually at present, relying on good will a lot of the time for timely disclosure. We know the laws mentioned above mean that new kinds of information will be coming into the public domain on a regular basis. That’s where using existing governance structures comes from.

Published data and industry standards

We also know that the data will be comparable and consistent, using standards defined with stakeholders in civil society and industry. That’s the published data, and industry standards part.

When data is consistent and comparable, even if it’s specialised information, it’s possible to translate this data into something more understandable for people who are not specialists. This is similar to how our Green Web Check results do for discussions about green energy online.

What next?

Between July 2024 and March 2025 we’re working on three main things:

- Research how to expand carbon.txt for this standardised data around green energy, and review the protocol with experts to improve it.

- Settle on a standardised, machine-readable way for firms to present this structured data and create validation tools and resources to support hassle-free disclosure

- Show how this data can be used in our Green Web platform to support green claims for hosting providers as an open source reference implementation so others can build on our work.

Are you an expert in the CSRD, ESRS, green energy or DNS-related security?

Throughout the course of our project’s research, we’re looking for opportunities to speak to experts in a variety of fields.

Carbon.txt marries two deep domains: sustainability regulation, and domain based internet security. We’re looking for people from either one. You don’t need to be knowledgable in both.

For sustainability regulation, we’ve published a very specific call looking for expertise on the EU’s CSRD sustainability regulations and how they will be adopted in practice. We’re looking for help now. Please take a look at EU sustainability regulation experts: can you help us?

For domain based internet security, in autumn 2024 we hope to speak to people who have a good understanding of domain based protocols like the ACME protocol as used by LetsEncrypt, Certificate Transparency as a way to some verify public security processes are followed, and ideally take up at a national level (for example the way security.txt is now mandated across public sector sites in the Netherlands). We’ll put a separate call out for that later down the line. But if you’re keen now please express interest via our form.

Keeping up to date

If you find this interesting anyway we’ll be posting updates as we go. You can follow along on our blog, on LinkedIn, or join our newsletter.