This post is based on a recent talk we delivered at FOSDEM, the largest open source conference in Europe (and if you speak to them, THE WORLD), where we explored the relationship between sustainability in a digital context, and accessibility online. If you are a web professional familiar with talking about accessibility, this post shows how you can use similar language to talk about sustainability too.

Background

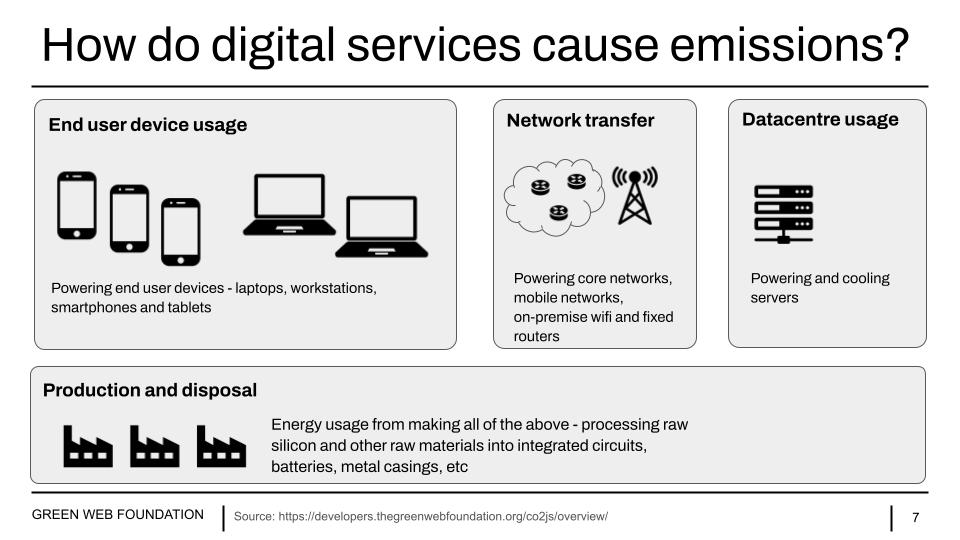

When we talk about a fossil free internet, you’d be forgiven for thinking it’s just about using green forms of energy like wind turbines and solar panels to replace burning fossil fuels to generate electricity.

This is definitely a large part of the problem we think about, but it’s not the only one. To get a better idea of the changes you might need, it’s helpful to draw a picture of the key drivers of carbon emissions.

Sure, we need to think about energy from the usage of infrastructure – the top row in the diagram below, but we also need to think about the energy and environmental impact of activity in the bottom row too though.

The embodied environmental impacts in hardware

As the diagram suggests, processing raw materials into working computers can be immensely energy intensive, because it often involves long, complex, multistage processes that can require incredibly high temperature heat.

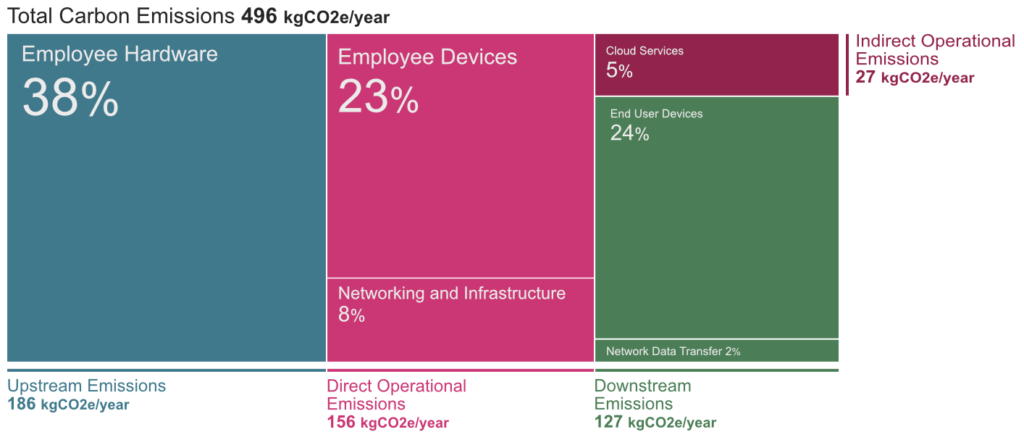

This really hit home when we looked at the emissions associated with operating our own digital services last year, where we used the exercise to take Scott Logic’s Tech Carbon Standard* for a spin. Here’s a tree map of our emissions breakdown:

You might have thought that the biggest driver of carbon emissions would be generating the electricity for the servers we ran, but this turned out to not be the case. The data showed us that the share of emissions attributable to operating the servers was actually dwarfed by the embodied carbon in the devices that our staff use – nearly two thirds of the measured carbon footprint came from the equipment on our desks.

There are a few reasons for this, but one of the simplest explanations is that in broadly speaking, while we have some control over where the power used to run our servers comes from, we have much less control over the power used when making hardware, and how carbon intensive the processes used to turn sand into silicon chips are.

In the longer term, we’re learning these can be decarbonised too, but in the short term, this means that making new hardware is unavoidably carbon intensive, and it’s one without too many obvious solutions.

However, this does help us understand where applying what we know about accessibility can come in.

A (very) brief recap of accessibility on the web

The field of accessibility for the web is by now quite established, and one of the landmark documents used to help understand how accessible a digital services is, is the Web Content Authoring Guidelines (often pronounced the Wuck-Agg…).

These guidelines contain a high level rubric for talking about website accessibility, called POUR – for perceivable operable, understandable, and robust. The guidelines themselves do a much better job of explaining what these mean but here’s the very condensed summary below:

Perceivable:

Perceivable in this context refers to making the content on a webpage perceivable to more than one sense – so you aren’t just relying on sight alone for example. Having a plethora of images on a page might be great for a sighted person, but what about someone who is partially sighted or blind, and using a screen reader? If these images have no form of backup description, these images can’t be perceived by them, because the screen reader has no cue to use, to help the user make sense of what is on the page – it’s not really perceivable to them.

Operable

You can think of operable as referring to how easily website controls can be operated. Lots of websites rely on a user having a pointing device like a mouse to help them select parts of a page or click on links. What if you have no mouse though, or can’t use a mouse? Does the website just stop being operable to these people? It’s good practice to support multiple ways of accessing controls, and well designed sites will frequently have keyboard support, to avoid this unfortunate situation. It also turns out that having keyboard support on a site allows a range of other devices that can simulate keyboards too, widening who gets to use the site – huzzah!

Understandable

When we’re looking at how understandable a site is, we might first think about interface design, and how intuitive menus might be. This is important, yes, but more often than not, a larger factor is simply how easy content is to read, and comprehend. The average reading age in your country may lower than you think, and a quick way to check is to see your country’s own guidance on target reading ages. Scotland’s own government guidance points to an average reading of 9-11, so when they want their content to be understandable to the whole country, they recommend simplifying language so it’s understandable at that reading age.

Robust

Robust refers to how a website degrades in less-than-ideal conditions, or in the face of errors. When pages are written in HTML (the lingua franca of the web), then browsers render them in a fairly robust way already. So, even when there are typos in the code, or things like external images of scripts failing to load, it will still work. You will still frequently be able to read content, or make a submission with an online form, even if things might not look very pretty.

By comparison if you write a page that only works in a specific browser, or relies on a specific library of software to have already loaded onto the page to work, then it’s much less robust. Only people who can rely on having that specific browser on their machine, or a connection fast enough to have that specific library loaded in time can access the content the page.

This also applies when people rely on javascript ahead of regular ol’ html. If there are typos or errors in this javascript code, then everything fails, and you can’t use the site at all – this much less robust.

Applying these to talk about sustainability

So, can we use these as a lens to help think about the sustainability of digital services? I think so, so let’s run through them in turn.

Perceivable

If content is designed to be perceivable using different senses (not just eyesight), then it means a page can be accessed and content consumed by a wide range of devices. Low end devices from a few years back can access it – in some cases even feature phones from the 90’s!

This means you’re not inducing upgrades, and causing people to buy new devices, just to access content that they should be able to access anyway. Which as we’ve seen now, has consequences in terms of carbon emissions.

Operable

Similarly, while we’re used to talking about operable in the context of making sure people with accessibility needs access digital services, it’s worth understanding that in the context of using online services, these accessibility needs are not always permanent, nor are they always tied to the person – they can be contextual as well.

If you have a phone with a broken home button for example, then you might not be able to operate the button, but that’s not because you have a physical disability – it’s the phone that is impaired. Having ways to support alternative inputs allows for continued use until it can be repaired, as opposed to requiring the person to buy a new device, just so they complete important transactions again.

Understandable

We know that one of the reasons people like digital ways to access services and information is that it can often be more convenient than other, more low tech approaches. If you can book a visit with your doctor and have a consultation via an online application, then it saves you needing to get in a car or on a bus to see them in person. This is sometimes called ‘channel shift’, because you’re using a different ‘channel’ to meet the same need.

But for this to be an option, you still need services that are intuitively designed and understandable so they can be used in the first place. Without this, people with relatively low digital skills, or people who are not confident readers may fall back to the previous ‘channels’, with the higher environmental impacts associated.

Robust

Finally, if you have robustly designed services, then the total range of situations where a digital approach works – as in where our lower carbon digital ‘channel’ is greener than the others – is greater. So, this means that take-up of your (hopefully) greener approach is higher, even in places where connectivity is bad, or in communities where people don’t have the latest and greatest devices. But it also means that we’re not unintentionally creating pressure to upgrade to new hardware just to complete a given task.

Does this lead to meaningful savings though?

This is where our things get a bit more complicated, because if you want to make a claim about delivering carbon savings, you often need a believable “business as usual” scenario to compare to for rigorous analysis – a counterfactual.

Doing so is outside the scope of this post, but we can use some “napkin math” to get an idea of what kind of impact we’re talking about.

Let’s refer to this paper Stipulated Smartphones for Students: The Requirements of Modern Technology for Academia, where researchers looked at how choices about the suite of software products students affected what devices students had to buy and use to complete their degree. This paper goes into detail about how software choice affected buying decisions, but for the purposes of this post, we can use some easy-to-follow maths to develop an intuition about the subject.

University sizes can vary, but it’s not uncommon to have large universities of more than 20000 students, and a nice round number like this makes the maths easier, so let’s use that figure.

We know that at least some students will need new devices to access services – once again, for easy maths, let’s assume 10% of students each year have to make this decision. Finally, we can refer to information in the public domain about the average embodied carbon in a new smartphone purchase by referring to Datavizta, from the lovely folks at french digital sustainability outfit Boavizta.

| No of students | 20000 |

| Update rate | 10% |

| Per-device embodied carbon | 84kg |

| Total carbon footprint | 168,000kg |

Continuing our “napkin maths” approach, multiplying these gives us a figure that adds up pretty quickly – 168 tonnes of carbon emissions, just from induced purchases, is not to be sniffed at!

This is still “napkin maths”, but the idea is still useful

Of course, this is just a “napkin maths” example to give an idea of why we need to think about the embodied carbon footprint of hardware as well as just looking at energy.

If you wanted to do this rigorously, there are a number of other considerations that make the maths quite a bit more complex.

But as a practitioner, there are some simple steps you can follow if any of this this made you think. If you:

- are explicit about the target ages of devices when buliding a digital service, and make sure it still works on them

- maintain a minimum level of accessibility throughout the service

Then not only are you making the service accessible to a wider range of users, but you’re also likely to making a more sustainable service too.

Further reading

As mentioned before, post is based on a 20 minute talk given at FOSDEM – the video recording is available online, and as is the slide deck used to present it, with further examples and useful content.

If you want to incorporate these ideas into your work, we provide training and consulting in this field – see our latest workshops, and see the other services we offer.

Finally, if you found this of interest, our Green Web Newsletter might be up your street too. Here’s to a more sustainable, more accessible web.